History of Westleton School

Plans for the school at Westleton were drawn up by Robert Appleton in 1842. His is an interesting example of how buildings were designed and implemented in the first half of the 19th century at a time when architecture as the profession we know it was in the process of emerging. When Robert Appleton married in 1817, he was described as a carpenter and builder; in the first census of 1841 he described himself as a farmer living on the Thorington Hall estate; and when he died in 1858 he was described as an architect and surveyor.

He was born in Prescot, Lancashire in 1791 but it remains unclear how or when he came to Suffolk. However, he married Susan Gooch in Long Melford although his own address at the time was Great Glemham. It’s also not clear how he made the step up from carpenter/builder to architect/surveyor, but there are interesting coincidences with the movements of the architect Thomas Hopper. He was working on Glemham House in 1814; he designed Thorington Hall built between 1817-19 for Henry Bence Bence; and he was engaged to design Kentwell Hall at Long Melford in 1826, although he may have been there earlier as an previous house on the site had burned down for he was a surveyor for the Atlas Fire Insurance Company. Bence acquired Kentwell Hall in 1839. So perhaps during this period, Appleton had impressed Hopper with exceptional skill as a carpenter and perhaps this led him, with support from Bence, to assist Appleton to attain the skills of a surveyor. Hopper himself had risen by such assistance, a not uncommon practice from the mid 18th century.

In the second half of the 18th century a great number of pocket-sized books were published aimed at showing builders how to delineate the essential elements of classical architecture, which helped disseminate the Georgian style. The wonderfully named Batty Langley, for example, wrote The City and Country Workman’s Treasury of Design, or the Art of Drawing and Working the Ornamental Parts of Architecture (1741) amongst more than twenty similar books. William Halfpenny and William Pain were other writers of this kind of popular book which enabled carpenters such as Appleton to design buildings such as Westleton School.

Appleton opened an office in Halesworth and is first recorded as undertaking alterations to St Mary’s Church, Halesworth, from 1823. More typically, perhaps, at this early stage of his career as a surveyor, he is recorded inspecting and making a valuation of a cottage at Friston in July 1825 and in 1833 inviting tenders for rebuilding a bridge on the Toll Road between Halesworth and Bramfield. By 1846, when he designed the first Halesworth Police Station, he had become a County Surveyor. A rather surprising early commission was to design the new church of St James in Dunwich in 1827 to replace All Saints, which had begun to topple over the cliffs. The plan shows this to be a simple rectangular box of a building that was reportedly ‘a stylish neo-classical design’. Perhaps it was his lack of refined understanding of the classical language of architecture that led to criticism from the sitting MPs and benefactors Michael and Frederick Baine, who set about having it re-made in the Gothic style before the church had been finished; the Battle of the Styles in East Suffolk!

In 1833 a government Treasury Minute was drafted to set out rules for distributing grants for new school buildings and in 1839 the Committee of the Privy Council on Education was created to oversee these grants. Two distinct bodies were established to claim grants; the Church of England’s National Society, and non-conformist’s British and Foreign School Society. The parish of Westleton was one of the first in East Suffolk to take advantage of this, the charitable foundation ‘Westleton Old National School’ being ‘founded by Deed of 14 February 1842’. The trustees were the vicar and churchwardens.

Sir Gervaise Blois offered a site described on a tithe map of c1840 as being an ‘unbuilt plot in a good central position between the Church, the inn and the pond’. In fact, it was a rather undesirable site at the bottom of the Village Green liable to flooding as a small stream or ditch conveyed water across the site when the pond overflowed. The Suffolk Chronicle of 23 July 1842 carried a notice inviting ‘persons willing to contract for Building School Rooms’ to inspect plans and specification at the house of the Reverend William Gardiner in Westleton.

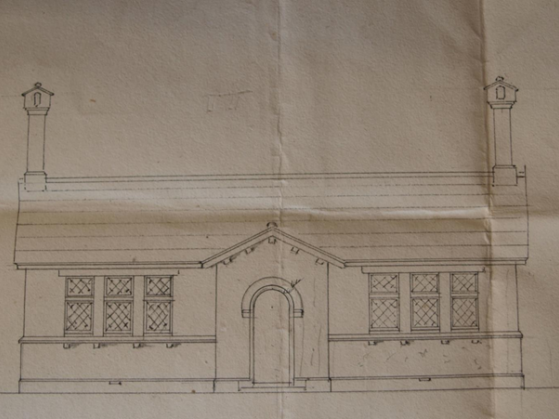

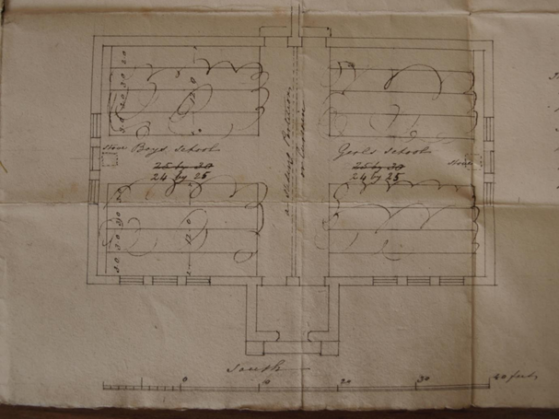

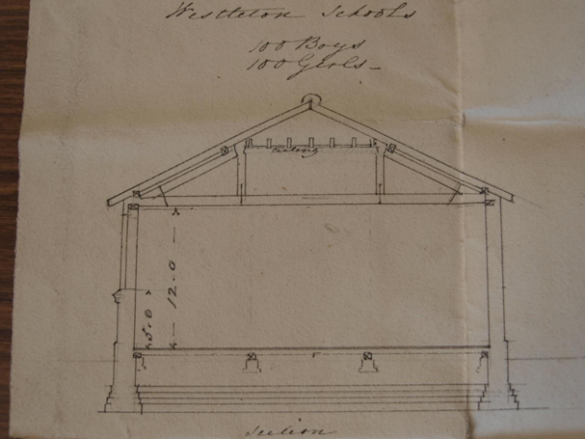

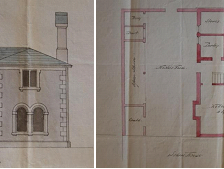

By this time, as we have seen, Robert Appleton was established as a surveyor and coincidentally in 1839 had reported on the state of repair of ‘coal sheds, cottages, gig house and stables’ at Blythburgh belonging to Blois.Robert Appleton’s drawing incorporated a ground floor plan, cross section, front and end elevations. His pencil drawing is quite rudimentary with no watercolour toning of walls on plan or elevation that was typical of architect’s drawings at this time. Appleton’s drawing gives no descriptive notes of materials or construction, but this was typical at this time when builders knew how to interpret drawings and build from them. Although no specification survives for Westleton School, that for Thorington Vicarage (1850) does, and along with general notes about quality of workmanship, includes clauses such as ‘Baltic red timber’ and ‘one bushel of slaked lime to one and a half bushels of sharp sand’.

The plan shows a simple rectangular hall to be divided into a boys half and a girls half by ‘a sliding partition or curtain’. A stove is shown at either end. The floor is shown divided into rectangles three feet wide and a note explains that this shows how ‘benches and desks…could be conveniently arranged …to meet the suggestion of the Committee of Education’. This is probably in response to the government’s Committee of Council of Education stipulating that ‘not less than six square feet be provided for each child.’ The scribbling over the bench layout seems to have been in response to a reduction in the

floor area from 50 x 60 feet to 48 x 50, which is how the school was built.

The cross-section shows brick footings about 4 feet below ground, the wall two-and-a-half bricks thick up to a plinth above ground level, 18 inches up to a plinth course at window cill level and one-and-a-half bricks above. Two sleeper walls support the floor joists and a Queen post truss for the roof,

although in place of the usual straining beam, there are ceiling joists running in the same direction as the purlins. This suggest that the roof truss was

intended to be exposed up to this point. The pitch indicated of about 27 degrees is rather shallow for slates and is drawn on a later survey drawing at

a more plausible 38 degrees.

The elevations show the school more-or-less as the main body of the school exist today, although the tall chimneys have subsequently been removed and the original diamond patterned glazed – leaded lights or iron frame? – windows have been replaced by casements. The end elevation shows the pair of semi-circular arched windows with a blind panel in between. Brackets shown corbelled beneath the window cills were probably not built. (Brackets were built on the later School House as well as imposts beneath the brick arches.) Although the school is usually described as ‘flint faced’, it is probably more correct to call it ‘pebble faced’ as it has smaller and more irregular stones pressed into the mortar than either the rounded ends of flints or the flat face of knapped flint. This is a local tradition that was used, for example, on the United Reform Church (1841) in Bramfield where Appleton had recently lived, and for Stonehouse Farm, Thorington, the house where he resided for the remainder of his life and which he may have designed.

The builder was a bricklayer John Brown (possibly of Middleton - 1841 census) who was known as ‘Dobbler Brown because of the liberal dabs of mortar on his trowel’! Suffolk white bricks were used for the quoins , window surrounds and main entrance porch. William White’s 1844 History, Gazeteer and Directory of Suffolk reports that the ‘National School…was erected in 1842 at a cost of£430’. A Jemima Brown was school mistress at this time.

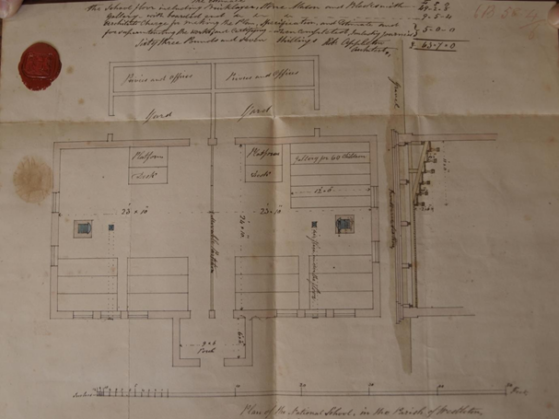

A small sketch section on the original plan suggests that stepped tiered seating was considered but not executed. For a drawing by Robert Appleton dated 9 November 1858 shows a revised plan layout and a cross section with such an arrangement for 60 children in one corner. (It is called ‘a gallery’, which has led to later misunderstanding.) A new floor on three sleeper walls is shown with a note stating ‘air flue under the floor’. New or repositioned stoves are shown adjacent to this, which suggests that ventilation had been a problem. The work cost £63 -7 -0, which included Appleton’s £5 fee. The school diary kept from 1863 reports a great number of illnesses and mortality rates were high at this time, so perhaps this alteration was part of attempts to remedy this. However, the diary continued to report deaths due to scarlet fever and diptheria throughout the 19th century. In 1891 new earth

closets were built in a further attempt to improve matters. Although it seems almost impossible that the 100 boys and 100 girls noted on the original drawing could be accommodated, the diary recorded 190 pupils on the books in 1882.

Since 1888 it had become a Public Elementary school with educational matters directed by East Suffolk County Council. The Ipswich Evening

Star of 19th November 1904 reported that a meeting of the East Suffolk Committee approved ‘a loan of £145 for alterations for

Westleton County School’, which almost certainly relates to the building of a single storey extension to form an Infants Class with its own cloakroom. Built in the same materials and style as the original School building, this is the current Committee Room and Kitchen. A drawing of 1912 by the County Surveyor shows new cloakrooms added which remain in the same position today. New urinals and earth closets were built in the yard and a new stove with boiler and radiator were installed in the original classroom. This work coincided with amendments made to the terms of the Trust dated 21 November 1912 whereby the school would be leased to the Local Education Authority, but the Trustees would ‘have control of the School Premises at all other times’. In this we see the beginnings of the building as a community facility. School numbers steadily declined through the twentieth century until there were only 30 pupils in 1967 which led to it being seen as unviable and it was closed that same year. A group of local residents, under the leadership of Morgan Caines and with the support of the Westleton Women’s Institute, decided to buy the building to use as a village hall. Funding was raised by selling an existing, but inadequate Women’s Institute hut and a small community ‘Gannon’ Reading Room.

In 1970 a charity was established to own and manage the hall on behalf of the local community. A number of outbuildings have since been erected– and some subsequently demolished - in the intervening years to cope with the expanded demands made upon the building as a village hall, including the village archive which is housed in a wooden hut. The building was listed in 1966? largely on the strength of what remains of the original building and its significant position in the village.

The neighbouring School Master’s house is without the direct scope of this Study. It was drawn by William Pattisson in c 1858 and is entirely more sophisticated. Pattisson announced his status as an architect by publishing a book Plans and Elevations of Cottage Villas and Country Residences, with Parsonage houses, Lodges and other domestic buildings in 1852.)